BYE, BYE, BLACKBIRD

No one gets through life without being hurt. To be human is to be hurt. All men and women have people or places that have negative associations. An offhand remark by a stranger or an acquaintance can resonate in our mind long after, years even, the unpleasant comment. A deed by a friend, a relative, or a parent can burn our soul. The bad experience results in a negative estimation of that person, who spoke the harmful words or did the hurtful acts. Often negative actions by others imprint in us a negative evaluation of ourselves. For 50 years I held on to negative memories and beliefs about my grandmother and my mother.

There are places where we were damaged. Some cities, towns, streets, schools, playgrounds, and houses become spaces we want to avoid. They are dreaded. We vow never to set foot in them again. Since I became an adult, my grandmother’s house and Rochester, New York, was my contaminated zone. This house in this city was where I grew to hate my grandmother and was consumed by anger against my mother.

I came to visit Rochester, NY, again because I was invited to present and speak in ”Q and A” session for the film “OF TWO MINDS,” by filmmakers, Doug Blush and Lisa Klein, about bipolar disorder. I am one of four people featured in the film. I would never have gone to this city if I hadn’t been invited. However, the presentation sponsored by NAMI Rochester provided the opportunity to revisit the place I was born and to which I had vowed in the past never to return.

The story begins: my father, the son of a prominent family, married a nightclub singer, Lynn Quinn, much to the displeasure of the family and especially his mother, Ann Carlton Davis. The family cut off my father and his new wife. They pressured him to give the first child of this marriage — my sister — to them because of my father’s enlistment in the Army Air Corps and the likelihood be would be killed in the Second World War, but my father survived the war and returned home, where he and Lynn had a second child, me, Carlton Morris Davis Jr.

My father had a job in Rochester factory and was going to school at night to finish his college education; but, unused to his reduced circumstances, he got himself involved in a felony scheme to steal cigarettes cartons from boat trains out of Canada. He was caught, and I was in the backseat of his automobile. Lynn came to the police station to retrieve me. My father’s parents retrieved him making a promise that they could get him off the felony charge if he left my mother. My father gave in. Lynn and I found refuge with my father’s best friend, Roger Fergusson.

The family hired detectives to watch the house where Lynn and I were living, and Roger was a constant guest. Lynn was singing in a local nightclub. She had Roger babysit me when she went off to work, but Roger had an alcohol problem. He would drink himself to unconsciousness, and one night I sneaked down the stairs naked because I had wet the bed, soaked my pajamas, and stripped them off. Roger was passed out on the couch. I went outside and began to run around the yard. I was about five years old and a hellion. It was winter with snow on the ground. The detective saw me and approached. I tried to hide in an overturned garbage can, but he pulled me out and took me to my grandparents’ house.

The grandparents tried to prevent Lynn from taking me back. She came to the door continually for weeks and demanded they give back her son. My grandfather would block the door, while my grandmother would restrain a wriggling and screaming me. I loved my mom. I wanted to be with her. We were close. She sang to me everyday. After a court hearing my grandparents were directed to give me back. Lynn, once she had me again, was fearful of the power of the Davis family. She took me to Connecticut to her sister’s house. This was in contravention of the court’s orders that I be kept within the State of New York.

My father came to Connecticut and with the help of the police took me from my Aunt Helene’s house. I screamed and yelled I did not want to go. I was taken back to Rochester to my grandparents’ house. The court decided neither my father nor my mother were acceptable parents. They made me a ward of the court under the control of my grandparents.

My grandmother disciplined me frequently because of what she considered bad behavior. I could play only in three rooms of the house, my sister’s bedroom, my bedroom, and an attic space where my sister and I could dress up in old clothes from trunks under the eaves. The rest of the house was full of precious family antiques and paintings of the apparently illustrious ancestors. At every opportunity my grandmother, would make me sit still on a Victorian red velvet couch with the portrait of General William Lee Morris, 1795-1880, looking down at me, and listen as the family’s history was recounted. If I moved, I was yelled at or slapped. I sat resentfully and wondered what my mother’s family history was. I was told if I didn’t learn how to behave like a gentleman, I would be taken away.

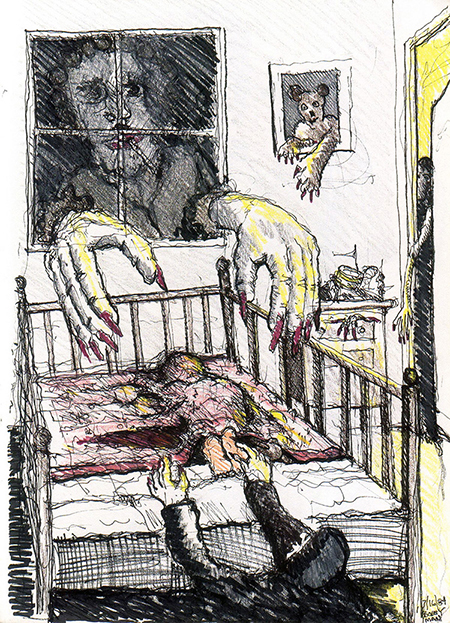

I had bad dreams in my bedroom. The bogeymen were going to reach in my window, crawl out from under my bed, squeeze through my door, or emerge from the pictures on the wall to snatch me away because I was a bad boy. My memories of the house are nightmares, which I internalized as negative perceptions of myself and converted into hatred for my family. This was the bad dream from which my innate mental illness grew. I now know that what I experienced as a child in this place is not the cause of my bipolar disorder, but it was the ground from which my mental illness blossomed.

Chinky the Chinaman,Genessee Rover,What my grandmother threatened took place. Disobeying her orders not to play in the downstairs, I broke a piece of crystal on a sideboard. My grandmother told my father and grandfather she could not put up with me anymore. I was too wild. I was taken to a foster home, where older boys sexually attacked me because I had long hair like a girl. My family had given me the nickname, “Chinky, the Chinaman,” because my right eyelid drooped slightly. I hated that name. At the foster home two older boys changed “Chinky, the Chinaman” to “Pinky, the Pussy,” and I was their plaything. One would hold me down and the other would rape me.

After six months of fear (the boys would threaten me with pitchforks as I collected eggs in the farm’s barn, if I dared to speak of their actions) and rape, my father took me from the foster home to his new wife and home in Corning, New York. The grandparents gave me to my father in violation of the court decree. I would remain a ward of the court until I was 21, but I could never speak of this to anyone for fear of Lynn. No one was allowed to mention my mother’s name. “Chinky,” was what my family called until I was 21 and demanded they stop. “Chinky” remained silent about the sexual attacks. As the years went by I forgot my mother’s name and what happened to me in the foster home until the memories resurfaced 30 years later. Never did I forget how much I hated that house, Rochester, New York, my grandmother, and my mother who I believed had abandoned me.

The return to Rochester allowed me to confront my past. I was anxious about making this journey. What I saw and experienced was a revelation. Rochester is a beautiful city. There is a tree-lined walkway beside the Genesee River in a downtown only moderately decimated by parking lots, with big attractive covered bus stops for protection against the winter snows. East Avenue stretching to the limits of the city is a broad green grass-lined street with many of the old mansions surviving, including The George Eastman House, home of the founder of Eastman Kodak, now an important archive of the history of photography. There is a delightful arts district along University Avenue with cafes and street sculpture anchored by the Memorial Art Museum with an astounding collection of American Art, and a Poet’s Walk outside along the street. Rochester looks to me like an attractive and cultivated place to live.

I went back to my grandparents’ house, and stood outside on the sidewalk looking at this building wondering if I could or wanted to see the inside. I pictured my mother banging on the knocker outside the front door and yelling at my grandparents to give me back, while inside I screamed to go to her. What the heck, I’m here, I thought, I might as well go and knock on the door to see if I could be let inside.

An attractive brunette with large glasses with a child about the same age as I was when I was made to live in this house, opened the door. I introduced myself and told her briefly that the house was my grandparents’ and I had spent a lot of time here when I was very young. This gracious young woman, a doctor married to another doctor, invited me in. She said she and her husband were very much interested in the history of the house. Following her and her son, I was shown around the house. The first thing that struck me was the corridor behind the front door that led to the living room and the staircase to the bedrooms above. The corridor I remembered was very long. My grandmother would hold me at the foot of the staircase while my mother attempted to enter. In actuality, the corridor is very short. I realized I carried into adulthood the perception of a child.

The new owner led me up the staircase to the bedrooms. At the door to the bedroom where I had been fearful of the bogeymen, she stopped, opened the door slightly, and reached for something hooked on the backside of the door. “Now I know what this is,” she said displaying for me an old skeleton key. The key’s loop was attached with string to a round tag that read “Carlton.” I was stunned! This is the very key my grandmother would use to lock me in the bedroom after I had misbehaved and was banished to my room. I began to laugh at the absurdity of the survival of this artifact from my youth.

Apologizing for mess in the house because her children played and did their school work all over, the owner guided me through the downstairs. Children’s coloring books covered the table in the dining room; toys were strewn about the living room. In what was my grandfather’s study and a room that my sister and I were forbidden to enter where the safe holding the sacred family documents were stored, I saw more children’s book and toys spread about. The safe was open. I thought how wonderful this was. The house that had been a stale mausoleum of family artifacts was now full of life. Instantly the demonic memories of the past were erased. I could think of this house now for what it was: the home of a happy family. I felt liberated.

I left Rochester feeling I had closed the loop on a piece of the ugly past, but my journey was not over yet. I drove to Ithaca, New York for a night with an old friend, a poet. She showed me a poem about Auschwitz, titled “Vanished Number.” In the context of the extermination of the Jews, my unhappy first years painful, as they were, I felt had to be understood in light of is this greater disaster. It was another shrinkage to my negative past. The next day I drove through Corning, New York, where I had lived from age 6 to 15.

My memories of Corning are also negative. My father, stepmother, and I lived across the street from the glass factory’s dump, which several years after my arrival was bulldozed and a school built on top. At school, bigger country boys beat me up. The name, “Chinky,” was the provocation. The town I thought was also a dump with liquor stores, bars, a smoke/magazine shop and a worn out Woolworth’s Department Store. In the smoke/magazine shore, I was caught for stealing a Playboy and severely disciplined by my father.

The Corning, New York, of 2014 is a far different place. The school over the dump is gone. Apparently, glass fragments surfacing from the soil were cutting children playing on the fields outside the school. The site is now a green field. The downtown is thriving, the main street lined with antique stores, restaurants, contemporary furniture stores, and a knitting shop. All this came about because of the Corning Museum of Glass, a big tourist attraction drawing thousands of visitors a year that shows historic and contemporary art glass. When I was a teenager the museum was small and featured Steuben crystal pieces that were given by the US government to foreign dignitaries and sold to the public. My family had several Steuben ashtrays. After the creation of fiber optic glass infused cables, the old museum morphed into a huge draw. I went away from Corning with my old viewpoint eradicated and replaced by an image of an appealing and bustling town.

From Corning I drove to Springwater, New York, a village south of Rochester, where I meet two nieces of a half-brother I never met. Peter Fergusson Lutz was the third child given up by my mother. He had a cyst on his neck at birth. My mother, unable to deal with his condition, gave him up to a nurse who also ran a foster home. The Lutzes adopted Peter, and I never knew of his existence until a few years ago when his daughter found me on the Internet. Peter died before I could meet him, but I know I would have liked him if we had met. He was an automotive inventor who restored old cars for a living. He was a lay minister of the local Nazarene Church and taught Bible classes. I was shown his annotated Bible, each page marked up with his thoughts and references to other passages of the bible.

I was delighted that out of all the tragic events of the past there existed: Laura, wife of Peter, woman engaged in her church and managing many units of elderly housing, Rebeka, an artist and teacher of foreign languages, and Joelle, an aspiring ceramicist. I found more family I liked and could love.

After a night in Springwater, I departed for Buffalo, New York, where I met my other half-brother Arnold Collier Jr., who also I had never set eyes on. My mother, after a second disastrous and contested common law marriage to Roger Fergusson, married Arnold Collier, a plating company owner in Buffalo. I knew of Arnold Jr. because of my search to find my mother back at the end of 1979, when I hired a detective to find her and visited her after 30 years in Las Vegas, Nevada. The meeting did not turn out very well, and I had no further contact with Lynn Quinn. She died in 2000. Arnold took me to see her grave.

Standing by my mother’s grave, I didn’t feel much emotion, but my anger was gone. I was glad to have this final chance to say goodbye. I had closed the loop on my troubled past. As I drove away I recalled the words of the song she used to sing to me. In her sultry voice, while tucking me into bed, she sang:

“Pack up all my cares and woes,

Here I go, singing low,

Bye, bye, blackbird.

Where somebody waits for me,

Sugar is sweet, so is she,

Bye, bye, blackbird.

No one here can love and understand me,

Oh, what hard luck stories they all hand me.

Make my bed and light the light,

I’ll arrive late tonight,

Blackbird, bye, bye.”

Her words became soft, barely audible as she left the room and turned out the light. She was gone all together now and no longer a negative force in my life. I forgave her, and I could love her. She had a hard and not too happy life, full of mistakes and hurt. And I thought of my grandmother, a woman who retreated into her family’s past clutching on to the objects that defined her, a woman whose husband was living with another woman when he was in New York City on work days, a son who was a total disappointment to her, and a grandson who hated her. She too was an injured person. I forgave her and I could love her.

I forgave myself for all the negatives I stored up. I am not the bad person that the experiences of the past had imprinted in my mind. I could love myself. I pitched away all my cares and woe and headed home to California. I felt restored, my resentments were gone, and the past was a closed loop. Make my bed and light the light, I’ll be home late tonight. Blackbird, bye, bye.

To anyone who harbors negative thoughts and feeling toward other places and people: I encourage you to confront them. Seek them out. Hear what they say today. See what they are today. I believe you will find them as ephemeral as a song sung into the air. I did. Bye, bye, blackbird.

Comment by Hermina S. Rosie on 25 September 2014:

Hi there, after reading this awesome piece of writing i am too happy to

share my experience here with friends.